Montreal, Quebec, Canada

In addition to the series of Covid-19 articles published on education and teaching in times of pandemic, I will interview today Marie-Jean, professor of francization at Center Saint-Louis school in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Judivan Vieira: What are the requirements for being a teacher in Canada, and how long have you been in the profession?

Marie-Jean: First, I must explain to you that Canada is a federation and that education falls under provincial jurisdiction; that is, each province has its own school system.

In Quebec, teachers (elementary, secondary, vocational training or francization) must have a bachelor’s degree in teaching. To obtain this diploma, one must study for four years at the university in the field that interests us and take many courses in pedagogy.

For my part, I am in my 34th year of teaching. I had the chance to practice my profession in New Brunswick for two years and another two years in Poland where we were training future language teachers (French, English or German).

Judivan Vieira: What is a francization course?

Marie-Jean: The francization courses aim to teach French to refugees, immigrants, or English Canadians living in Quebec so that they can integrate in the job market, pursue studies or simply integrate into Quebec society.

Judivan Vieira: Why did you choose to be a francization teacher?

Marie-Jean: Basically, I studied to teach history in high school. In New Brunswick, where I started my career, I had to teach history as well as French to young Anglophones. So I specialized in French.

When I returned to Quebec, I applied for a position in high-school history, but I was offered a contract in francization because there was a great lack of teachers in this field. I would therefore say that I did not choose francization, but that it was a combination of circumstances that brought me there. I must say that I am very happy because I loved all these years spent teaching and promoting the French language. As you can’t teach a language without teaching the culture it conveys, that’s perfect for me.

Judivan Vieira: Can you say which Canadian provinces are adopting the francization course?

Marie-Jean: Since Canada is an officially bilingual country, the teaching of English or French as a second language is compulsory at the elementary or secondary level in all provinces. As we accept many immigrants and refugees each year, all provinces owe it to themselves to teach the official language of the province. I must specify that if Canada is a bilingual country, the same does not apply to the provinces which are all unilingual (English) except Quebec which is unilingual (French), and New Brunswick which is the only bilingual province.

Judivan Vieira: Who is the French language course aimed at and what subjects are taught? Is the course compulsory for anyone coming to live in Canada?

Marie-Jean: The francization program is intended primarily for adults 18 years of age and over. We only teach them the language and of course we also talk about our culture to promote their integration.

For young allophones between the ages of 16 and 20 who arrive here and who do not have a high school diploma, they are offered a “French transition” program. They mainly study French as well as some subjects that will allow them to integrate regular courses for adults in order to obtain their diploma. Here is what the Cssdm says: “The French transition studies program is aimed at young immigrants aged 16 to 20 whose fluency in French is insufficient to allow them to continue their secondary school education. Various knowledge and skills are acquired: oral and written communications, knowledge of the language, general knowledge of Quebec and Canadian societies. “

For the other children, we put them in a reception class, where they mainly learn French. They generally stay there for a year (or two if necessary) and then join the regular system, but generally a year behind young Quebecers.

Judivan Vieira: Is the francization course program established by the provincial government, or is it a determination by the central government?

Marie-Jean: As education is a provincial prerogative, the government of Quebec establishes the program.

Judivan Vieira: Can you say if the provinces that adopt English also recommend a course in acculturation to the English language?

Marie-Jean: Yes, the English-speaking provinces offer a program similar to that of Quebec.

Judivan Vieira: How many francization schools are there in Montreal, and what results can be reported in relation to the students who took the course, in Quebec society?

Marie-Jean: I cannot say how many francization centers there are in Montreal, because several school service centers offer such courses as well as the MIFI (Ministry of Immigration, Francization and Integration), as are many community centers.

It is very difficult to follow up because few adults start at level 1 and go to level 8. For various reasons (family, work, studies, moving, etc.), they generally leave the centers after a few sessions.

Judivan Vieira: How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected classrooms? Was it necessary to adopt the online or hybrid classroom system?

Marie-Jean: During the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020), the government closed all schools, including CEGEPs and universities. All the francization centers, therefore, found themselves giving their courses online until September.

Numerous students gave up because learning a language behind a screen was really not ideal, not to mention that several teachers, me the first, did not have the necessary computer skills nor the adequate equipment (high-performance computer, digitizer, headphones, office or quiet place) to give 4 hours of lessons daily.

In addition, no one knew the ‘Teams’ platform that we had to use, and so we had to take many online training courses to learn how to master it.

Many of our students did not have a computer, and some others did not know enough about computers to continue learning the language.

In the fall of 2020, the centers reopened while keeping a day online in case the government decides to close schools or in the event of a major outbreak in a classroom or school.

It was probably necessary to close schools or do hybrid courses to limit the spread of the pandemic. It was very difficult for the morale of the professors and students, especially for those who lived alone or who were psychologically fragile.

Judivan Vieira: In your analysis, is the effectiveness of the classroom or the online course system more effective?

Marie-Jean: In my opinion, there is no doubt that the classroom is the ideal place for effective teaching of French. Having one day online per week (which is likely to stay, even after the pandemic) can allow students to work at their own pace (writing, reading, researching), but it quickly reaches its limit. In class, we can correct pronunciation, see students’ eyes if they have understood, and explain grammar more easily with the use of the board.

I would never have become a teacher if I had been told that I would spend my days in front of a screen. I need to create links with my students, to see them progress, and to make them love this language that they will use on a daily basis and which will allow them to take their place in Quebec society.

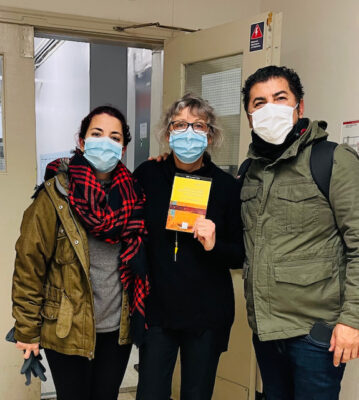

Photo from personal archive

Photo from personal archive.

Camila Vieira(left), Teacher Marie-Jean(center)